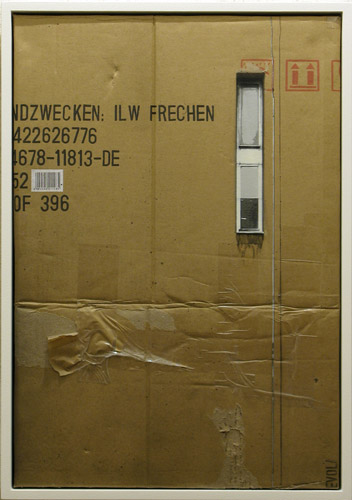

Evol, Lichtenrader 32. Spraypaint on cardboard, 60 x 40cm

A Conversation with Evol

by Carson Chan

Evol, Lichtenrader 32. Spraypaint on cardboard, 60 x 40cm

Carson Chan

Much of your work today is made indoors. Like most street artists, did you begin outside?

Evol

I have always been obsessed with drawing. When I was 14, I started drawing a lot with charcoal. I hated cleaning brushes, so once I found out about spray cans – which are perfectly portioned, premixed, and portable – I discovered that I could paint anywhere outside. It was really about making images wherever you wanted, without asking anyone, and anyone that passed by could see it. This was 1991, so I was 19 and still living in my hometown, Heilbronn, in the southwestern part of Germany. The idea was very simple – I was just walking around looking for interesting architectural moments and finding them. I would just draw whatever came to my mind. After a short time, I got to know the graffiti scene in Heilbronn, which was very small. Though we all shared an interest in painting outdoors, I never felt at home with graf writers – though everything I’ve done since then has developed from graffiti. I never liked hip-hop all that much, which is a big part of graffiti culture. I listened to metal or hardcore, lots of Slayer.

CC

When did being an artist become part of your identity? In other words, when did you start calling yourself Evol?

E

By accident. In graffti there are hip-hop jams where people come together to write. I was invited to one of those jams in Heilbronn, and when I was asked what my name was I just made something up. I was wearing Evol brand skater shoes then, and of course I knew the Sonic Youth album of the same name.

CC

So it had nothing to do with spelling ‘love’ backwards.

E

I mean, that’s why Sonic Youth called their album Evol.

CC

I was hoping it was some kind of tradition relating to Blek Le Rat, who pioneered the use of stencil in street art in many ways, and who called himself Rat partially because it’s an anagram of ‘art.’

E

No – but still, having one word that means the opposite read forward and backward is interesting to me.

As a graffiti writer, I got paid to do some commercial jobs, but by 1994 or 1995 it got a little boring. At this point I started my formal studies in product design, which was sort of a basic education in aesthetics, rules and learning new techniques. I spent a lot of time in my studio, and in this new environment, I started to rethink what could be done inside. Stencils seemed like a good option because you don’t have to mix colors, and complex effects can be developed from your computer to your printer in a couple of hours. I really love the surface and the appearance of flat colors in stenciling. It has the look of something printed – something that looks simultaneously manmade and machine-made.

After my studies, I worked in a product design firm in Stuttgart. In fact, I worked as a freelance product designer until 2008. I designed everything from watches to vacuum cleaners, whatever was asked of me. I enjoyed the switch between doing street art and then next week having a job in a real business. This really gave me a way to think about each project from different angles. In 2000, after a year in Stuttgart I had to move to Berlin; the prospect of being stuck in Stuttgart for the rest of my life was too present. I had a job there – life was a little too nice. So I moved to Berlin and had nothing, but I just wanted to be here, going back to Stuttgart only for specific projects. In Berlin, I really started cutting stencils and experimenting with the technique.

My aim has always been to reflect what was going on around me through images. The work with buildings, like the Plattenbauten project (2004 onwards), deals with the idea of doing something without having one’s name attached to it. Plattenbauten, these buildings with bland, featureless prefabricated slab façades you find everywhere in Berlin are great because they too are anonymous yet they have so much character. I’ve always loved walking around the city, looking for architectural moments that spoke to me. The surface of the city is something on which I can communicate both to a small circle of street artists, and to society in general. I always noticed these grey electrical boxes as I walked around Berlin, and I just had an impulse to do something with them. I also like that they’re usually pretty dirty, that they accumulate color and texture simply from sitting outside. The same goes for the cardboard pieces. The cardboard I use is all found material. It has markings from use and neglect: bits of tape, writing, scratches, signage. These accidental markings signify experiences that have little to do with the cardboard box’s intended use.

CC

Pieces like Mostroinvasion (2003) and Adidas Security Force (2004) were stenciled directly on packaging material and were made when you were much more involved in product design. In Mostroinvasion, a Puma sneaker shaped tank sitting in Alexanderplatz was stenciled onto a disassembled shoebox. With these works, you’ve constructed a matrix of war, commercialism and public space.

E

During that period, a sneaker shop in Berlin asked me to paint something for them. In my research, I found out about sneaker nerds, people who spend their time hunting for limited edition sneakers. I found this really bizarre. Collaborating with a brand that promoted a senseless kind of consumption was an opportunity to critique a perverse sort of blind imperialism.

CC

Can you speak more specifically about the political ambitions in your work? I’m interested in your Swastikea project (2005), where the image of an Ikea style table arranged to form a Swastika is stenciled on various wood veneers. Within your practice, it represents a conflation of your background in product design and your practice of communicating socio-political ideas through imagery.

E

It’s not that I’m a classical left-wing Maoist, it’s more that I try to walk around with open eyes. Any random flat is filled with products from Ikea. Most people, especially in the West, long to be individuals, yet they purchase this individualism from the same company. They unwittingly reproduce a totalitarian ethic. I don’t have ambitions to express political opinions, but my work does deal with political ideas. I’m not trying to draw a line between the Third Reich and consumer culture – which is difficult and problematic. This was a caricature of an idea.

CC

During that time were you working as Evol, or more anonymously?

E

I get schizophrenic sometimes. I don’t paint trains or tag under Evol. Evol is more of a legal identity I take. Even the Plattenbauten project, authored under Evol, was sprayed on transparent stickers so these the electrical boxes were never permanently marked. You start developing several identities. When I tag, I’m someone else. When I work as a product designer, I work under my birth name.

CC

Let’s talk about the question of identity. For someone who works in multiple fields and on multiple levels of legality you must work around this constantly. Street artists are often known by pseudonym, which is never associated with a legal citizen. They’re detached from a greater system of governance. Showing within a gallery, as opposed to in the public sphere, brings with it a different set of implications for the artist’s identity. Outdoor, urban pieces address viewers, any random passerby, as part of a general public. Whereas pieces exhibited in a gallery address a specific audience that includes art critics, curators, gallerists, and collectors. Pieces done outdoors can be gone in a matter of days, while pieces exhibited in galleries are available for extended periods of contemplation. Gallery pieces are subject to an institutionalized form of viewing and criticism that implicates the artist as liable for the reception of his work. How has this shift in audience affected your process?

E

My practice, which included product design, tagging, as well as art has always required me to negotiate between systems. Within the street art community there is a notion that street art should be on the street – which is basically true. I don’t necessarily see myself as a street artist as much as simply an artist who does things for the street as much as I do things for the gallery. I’m a different artist depending on where I’m working.

CC

So this goes back to the schizophrenia. Do you still do work outside?

E

It’s very important for me – but it has become a time issue. I feel like something is missing after not having painted outside for a while. As I said, when you’re on the street, you feel the pulse of society, and that’s where my topics come from. So it’s about seeing how people behave around each other. The streets are where my ideas come from.

CC

When you first moved to Berlin did you live in a Plattenbau?

E

You want to know how the Plattenbauten project came about – In fact I was so broke at that time because the product design firm I was working for in Stuttgart was on the verge of closing and they couldn’t afford to keep paying me. I was so broke that I had to go to the job center. The closest one to where I lived was in the former East Berlin suburb of Lichtenberg, and the the job center was in a depressingly ugly Plattenbau. I was so adamant about not going back to this ugly building that I became much more resourceful in terms of finding work!

CC

But the care you used to make these sculptures celebrate the Plattenbau’s architecture rather than dismissing it. You consciously preserve their grimy surfaces and render the endless, obsessive repetition with finely detailed windows. They seem to propagate a memory of a Berlin from right after the wall fell, when buildings all over were still unrestored, when pockmarks from bullet holes and other marks of neglect reflected a rich history and a unique context. Mostroinvation, which you made six years ago, relates to Berlin as a historical site – the modular façade of the GDR-era Kaufhaus pictured in your piece is now removed. To remember it and to depict it within a critique of commercialism is to take a stance on the visual environment and its participation within abstract systems like the economy.

E

I wanted to make a harsh, brutal image of time that is easy to understand. When Germany was reunited, they wanted to remake and control its public image in order to attract tourists. Tearing down the Palast der Republik, the former East German seat of government, to rebuild the Kaiser’s palace is part of this same mentality. It’s so stupid to create a kitsch version of the past. It’s an example of how the politics practiced here is about visualizing outdated sentiments in the urban sphere. So you’re right, I do have a strong desire to remind and celebrate Berlin’s urban history.

CC

How are you conscious of the different audiences you engage with on the street and in the gallery?

E

When you do stuff on the street, you don’t know your audience. You know they are there, but you just have to stand on the street and see how people react to it. Sometimes they rip things down, sometimes they repaste them. I don’t make art for a specific audience. Whether its legal or illegal, it makes very little difference as to why I’m making art. I’m doing it for myself, but also in order to show it.

CC

What drew you to only focus on architecture, specifically the architecture of Berlin?

E

I like that history is visible on buildings here. It’s far more interesting when there are stains and remnants of posters. Painting windows on found cardboard and scrap metal creates a similar effect. My work is often a reflection of the area in Berlin where I’ve lived for the past eight years. When I first came, everything was grey and brown and you could even see bullet holes from the war. Now, everything is cheaply painted over with yellow paint. I’m very conscious of marks on public surfaces. Writers and graffiti guys make obvious, explicit markings, but less obvious ones like old signs are also part of urban communication. I can tell who’s been there, who lives there. Clean surfaces don’t speak to me, so recording these marks is a process of visually remembering the charm of a place that will soon be painted over.

CC

The markings on the found cardboard change scale the moment you stencil a certain size window next to them. Bits of old tape, wrinkles, creases, and barcodes all transform into architectural elements. The texts on the carton, “handle with care” or “fragile” suddenly become urban commentary when you paint a façade on the same surface. Also, the fact that the cardboard is found rather than bought suggests a commentary about our culture of disposal. Like what you said about the Palast der Republik, community, or common history, can easily be disposed of because it can just as easily be purchased. In the Plattenbauten project, and subsequently in the famous installation you made at the Flamingo Beach Lotel (2007), the scale of the perception shifted urban to personal. In the cardboard works, it seems to be the opposite.

E

When a radio interviewer saw the Plattenbauten at an art fair, she described things about the pieces that didn’t really exist, like flowers in the windowsills – but they were things she saw because the piece was able to evoke her actual memory of these buildings, populated with people and their daily trappings. I’m continually fascinated by how these ‘found’ markings on either electrical boxes or cardboard can become something else through miniaturization.

CC

They act as a point of convergence for several contemporaneous but distinct spheres in our everyday life. Suddenly the visual logic of global shipping (ie. barcodes, “fragile” warnings) is conflated with those of our daily living. That which was distant and abstract all of a sudden becomes personal and intimate. When you miniaturize buildings, you immediately objectify our habits of viewing the built environment – we see ourselves seeing.

Your background in product design, where you had to be conscious of what consumers wanted to buy, sits well with your use of packaging material like cardboard, but it was great to see this dimension of your practice appear in the tagging project called Advertising Space 4 Rent (2006).

E

This project came from thinking about the double standards in public space – how graffiti is banned yet billboards and advertisement are allowed to proliferate. There’s so much visual pollution. That’s why I thought to paint “Ad space available for rent” on random pieces of trash.

CC

It’s seems impossible to compete with advertisement as visual information in the urban environment.

E

At the same time, graffiti is also like advertisement. Most graffiti guys are only interested in throwing their name on walls – getting a name up – to become recognized by the public.

CC

Artist and writer Cedar Lewisohn wrote in his seminal book on street art that tagging is essentially branding. It’s the dispersal of a visual form without any content.

E

That’s half true. There is content, but it’s only readable to a very elite scene, so yes, to the general passerby it’s content-less.

CC

I’m interested in repetition in your practice. Stenciling is a technique, like photography, that inherently suggests the possibility for an image to be repeated infinitely.

E

A tag becomes meaningful when it becomes ubiquitous. I remember being struck by the endless windows of the building in Berlin that formerly housed the inner state police. There was a pretty direct relationship between seeing the modularity of windows and understanding the modular nature of stencils. I have been using the same two stencils to make windows since 2004.

CC

Not only is street art seen as an outsider art form within mainstream contemporary art, but some of your work even appears to be outsider street art – meaning your practice seems to exist in a position separate from the traditions of the street art scene proper. I say this because in some of your depictions of urban spaces, we can see graffiti tags on your buildings. Making a stencil of a tag is a really bizarre concept to unpack within the traditions of street art. Like making a painting of an etching, or a tapestry of a photo, with this particular action of stenciling a tag you raise a lot of self-reflexive issues concerning the discipline and institution in which you operate. Stenciling a tag is not simply a combination of techniques – but I see it as evidence of a meta-critique; a consciousness of your position that reveals itself through re-representing its image.

E

I don’t make art while reflecting on how I, as an artist, will be seen. I don’t know whether I consciously take this distance from the traditions of street art.

CC

But your work seems to be reflecting on street culture, while still operating within it. Most street artists are not reflecting on the scene, they are simply in the scene. You’re making work that is about the work.

E

I think that many street artists are just pushing their names – advertising. Tags are logos that are repeated over and over again. That’s as boring for me as advertising from big companies. I like to see people playing around in, and with public space. I want to understand how people are aware of the space in which they work. I’m interested in adding to and creating something where the result is more than the sum of its parts. Through subtle interventions, it is possible to change the meaning of a space. I enjoy that – and I enjoy the awareness of that. Walking around the city then becomes an exercise in noticing these different moments in the urban environment. Anything that catches your attention, really. An image painted on windows that appear half hidden because the window is opened, for example, is enough to make me take a second look. The nicest stories from the street happen by accident.

CC

By taking on the role of an observer in both the street and gallery art worlds, by being distant from the disciplines in which you operate, do you run the risk of being neutral? In a way, the “dirty” part of street art is missing in much of your work. Part of what’s nice about experiencing street art on the street is the knowledge that someone secretly made the piece with the risk of being punished for it. The adrenaline of operating outside the rules of society, within society, gives street art its power.

E

You can’t bring this energy into stenciling. Stenciling is such a slow process – especially when you have twenty layers of color on top of each other. It’s not spontaneous in the same way, but it still works with an understanding of how accidents can affect the outcome. I don’t need this energy in my stenciling – in any case, I still go out tagging.

CC

How much do you associate your own work with the traditions of street art in general? You mentioned that you painted on trains – is this a reference to the origins of street art in 1970s New York?

E

I’ve always found it strange that street artists today want to be like those guys in New York twenty years ago. I’m here in Berlin! I was born in West Germany. I find no need to act like a New Yorker from twenty years ago. My work follows from my personal background. I’m aware of what is happening in the street art scene, but I’m not necessarily looking for my own personal role within it. One of my favorite artist is Martin Kippenberger. I really love his humor. Humor is very important for me.

First published by Wilde Gallery, Berlin, 2009.